As we begin 2025, and in anticipation of the completion of ICANN policy activity for the New gTLD Program: Next Round, the Interisle team looked again at our 2024 Cybercrime Supply Chain study. For that study, we collected spam, malware, and phishing reports from eleven blocklisting services and from these sources identified over 16 million cybercrime events. We hope that the measurements, metrics and observations of those events we present here will inform ICANN and other policy makers as they consider policy for Round 2.

Abuse domains reported per TLD

The total counts (raw numbers) of domains associated with spam, malware, and phishing is a basic and familiar measurement. We begin with .com, the largest TLD (Top-level Domain). For our 2024 study, the most recent ICANN domains under management (DUM) monthly figure for .com was 154.7 million. When we ranked TLDs by total cybercrime domains reported, .com topped the list with 3.2 million cybercrime domains reported.

The .com is an extraordinary outlier in the domain world. It has more domains under management than all the country-code TLDs (ccTLDs) combined and more than four times more than the new generic TLD (gTLD) program. 3.2 million cybercrime domains reported is a large number and it should not be dismissed lightly. No single TLD had more than one million cybercrime domains reported. However, it represents some 2% of .com’s registered domains.

We next use a scoring metric to better understand how this finding .compares with other TLDs in the domain namespace.

Abuse domain score per TLD

Domains under management (DUM) and abuse domain numbers for .com yielded a yearly TLD cybercrime domain score of 209.3. This score represents the number of cybercrime domains per 10,000 domains under management in the TLD for the yearly period and it allows us to .compare large and small TLDs even-handedly. Some .comparisons of yearly cybercrime domain score against other gTLDs worth noting:

85 TLDs had a higher yearly cybercrime domain score than .com: 64 new gTLDs, 5 legacy TLDs, and 16 ccTLDs.

23 TLDs had yearly cybercrime domain scores that were more than five times that of .com.

The .top TLD, ranked second in most abuse domains reported, had ~830,000 domains reported for cybercrime on a base of 2.8 million domains under management. This yielded a cybercrime domain score of 2952.3, fourteen times larger than .com’s score.

30% of .top domain under management registrations were reported as cybercrime domains, whereas .com had 2% of domains reported. The .com TLD would have had over 46 million cybercrime domains reported if its score were the same as .top.

Several small TLDs that had low domain scores in previous years did poorly in 2024 because cybercriminals targeted them as a domain resource for spam campaigns involving large numbers of domains; for example, the domain scores skyrocketed previously unranked .ooo (39,050 DUM, 5661.2 score) and .cam (42,639 DUM, 3688.2 score) into the top five TLDs ranked by domain score.

This finding is consistent with our phishing studies over 4 years that show that TLDs with small DUM are more vulnerable to a single or small number of bulk registration events.

To understand whether and where cybercriminals persistently register domains for cybercrimes, we’ll next look at abuse over time.

Year-over-year increase of abuse domains per TLD

Over 8.6 million unique domains were used in cyberattacks .compared to 4.8 million last year – an 81% increase. Looking at individual TLDs, cybercriminals exploited 208 TLDs. Notably,

138 TLDs had an increase in cybercrime domains reported:

More than one-half of these (78) were new gTLDs.

72 TLDs grew by more than 81%.

30 TLDs had increases greater than 250%

the largest percentage increase was BOND (2,897%).

The .cc, .club, .xyz, .vip and .top TLDs had year-over-year increases of 662%, 568%, 562%, 428% and 302%, respectively.

On the positive side, 68 TLDs had a decrease: 43 of these were ccTLDs.

Composite marketplace analyses tell another story

Our research has consistently identified significant statistical differences across the legacy gTLDs, ccTLDs, and new gTLDs. In our 2024 study, we reported several findings regarding the new gTLDs delegated in Round 1. One finding that attracted media attention (SCWorld, KrebsOnSecurity, Domain Name Wire) was that “cybercriminals continue to flock to new generic top-level domains (new gTLDs) as preferred suppliers of naming resources.”

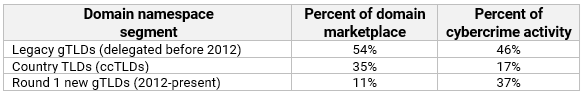

Our data showed that the legacy gTLD and ccTLD market segments have proportionately less cybercrime activity than their overall percentage of marketplace would suggest.

Raw counts per namespace segment

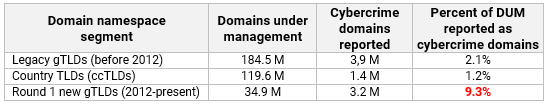

We looked at the raw counts of the three market segments in TLDs for which we processed cybercrime activities in the period Sep 2023 to Aug 2024:

(Note: we use ICANN as a monthly source of the number of registered domains for each TLD)

The 3.2 million cybercrime domains reported in the set of new gTLDs for which we identified cybercrime activity is nearly the same as the .com TLD alone. It .compares unfavorably to the 3.9 million reported in the set of legacy gTLDs. It’s important to note that the 34.9 million DUM for the set of new gTLDs is 18.9% of the combined 188.6 million DUM of legacy gTLDs.

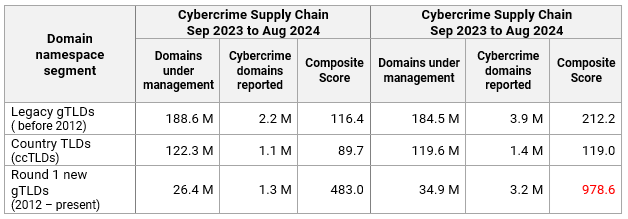

Domain score per namespace segment

We .compared the yearly cybercrime domain score of the three market segments. We again used TLDs for which we processed cybercrime activities for two year-long periods.

The ccTLD market segment had the lowest yearly cybercrime domain scores. The score for the combined legacy gTLDS nearly doubled, as did the score for the combined new gTLDs.

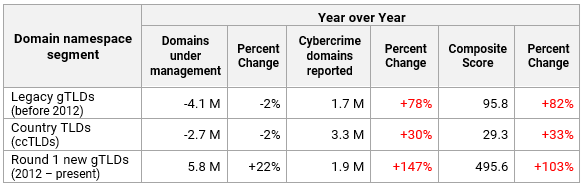

Year-over-year increase per namespace segment

Cybercrime activity in the ccTLD market segment has subsided. Much of this may be attributed to the shutdowns of the Freenom .commercialized ccTLDs, but many ccTLDs have registration restrictions and higher registration fees and are thus less attractive to cybercriminals than those gTLDs that offer free or cheap registrations with no restrictions.

Summary

The volume of cybercrime activity has increased year-over-year across the domain name space.

While the namespace overall suffered an increase in cybercrime domains reported, several TLDs showed decreases. This suggests that cybercriminals were TLD-agnostic: they exploited certain TLDs for a period, abandoned them and moved on to a different set. In some cases, they returned to previously exploited TLDs. We observed this behavior in the new gTLDs more than the other namespace segments. We note that this behavior is consistent with what we observed over 4 years in our phishing studies.

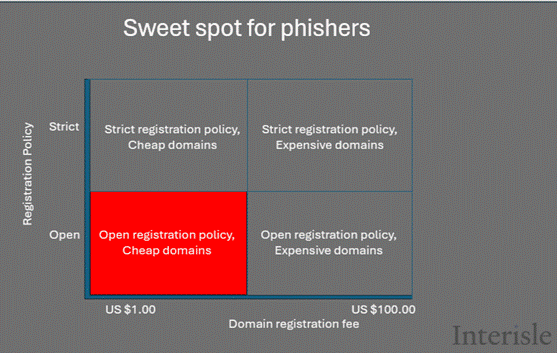

In our 2024 study, we explored the effects of imposing identity verification requirements on domain registration. We also explored pricing and found that the combination of open registration policy and cheap registration fees make the gTLD space generally, and the new gTLDs, more attractive. These findings were corroborated in an ICANN-sponsored study, Inferential Analysis of Maliciously Registered Domains.

The Round 1 new gTLDs have a higher concentration of cybercrime activity in a significantly smaller “population”. This concentrated exploitation of name resources must be considered in policy development for Round 2.

Recommendations

In our Cybercrime Supply Chain 2024 study, we recommended that ICANN should consider the history of cybercrime activity in new TLDs that offer open registrations and cheap domains carefully as it processes applications. The objective of fostering competition has arguably led to unanticipated and unwanted consequences.

Delegating more generic TLDs with open registrations will merely increase the availability of cheap domains and further expand the already plentiful opportunities for cybercriminals. ICANN should instead consider delegating TLDs that offer more secure alternatives such as .bank and .pharmacy, and TLDs that serve geographic (e.g.,.wein, .cat., .tirol) or community needs (e.g., .music, .radio) and impose nexus or verification requirements.